Millegan Stews

9/20/01

. . . quickly made the White House into the chief flapdoodle factory in the nation . . .

An excerpt from:

America in Crisis

Daniel Aaron editor

Alfred Knopf ©1952

The primary significance of the war for the psychic economy of the nineties was that it served as an outlet for aggressive impulses while presenting itself, quite truthfully, as an idealistic and humanitarian crusade. The American public was not interested in the material gains of an intervention in Cuba. It never dreamed that the war would lead to the taking of the Philippines. Starting a war for a high-minded and altruistic purpose and then transmuting it into a war for annexation was unthinkable; it would be, as McKinley put it in a phrase that later came back to haunt him, "criminal aggression."

. . .

The dynamic element in the movement for imperialism was a small group of politicians, intellectuals, and publicists, including Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Theodore Roosevelt, John Hay, Senator Albert J. Beveridge, Whitelaw Reid, editor of the New York Tribune, Albert Shaw, editor of the Review of Reviews, Walter Hines Page, editor of the Atlantic Monthly, and Henry and Brooks Adams.

They were much concerned that the United States expand its army and particularly its navy; that it dig an isthmian canal; that it acquire the naval bases and colonies in the Caribbean and the Pacific necessary to protect such a canal; that it annex Hawaii and Samoa. At their most aggressive, they also called for the annexation of Canada, . . .

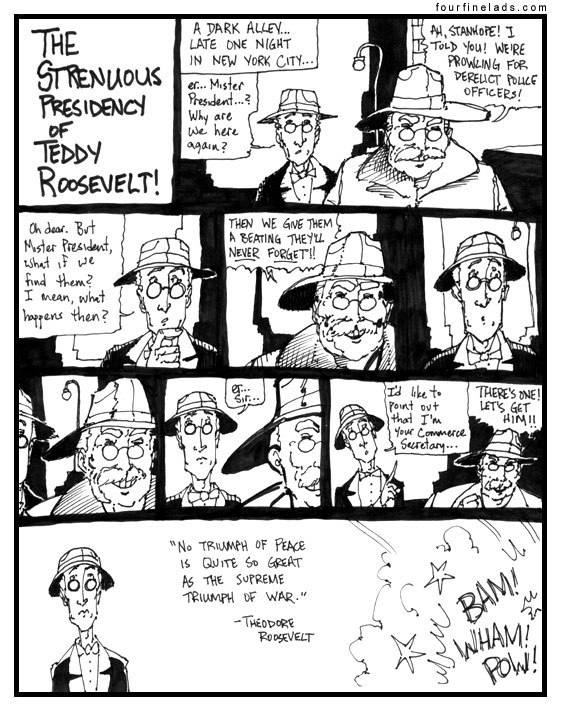

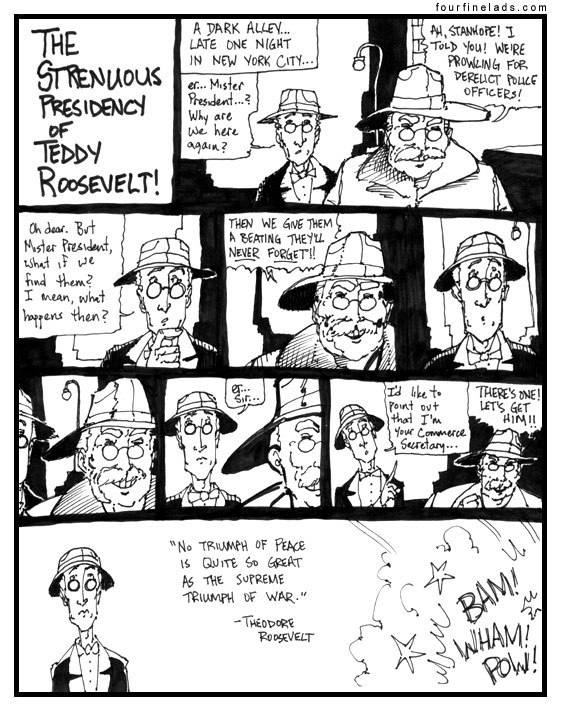

The central figure in this group was Theodore Roosevelt, who more than any other single man was responsible for our entry into the Philippines. Throughout the 1890's Roosevelt had been eager for a war, whether it be with Chile, Spain, or England. A war with Spain, he felt, would get us "a proper navy and a good system of coast defenses," would free Cuba from Spain, and would help to free America from European domination, would give "our people ... something to think of that isn't material gain," and would try "both the army and navy in actual practice." Roosevelt feared that the United States would grow heedless of its defense, take insufficient care to develop its power, and become "an easy prey for any people which still retained those most valuable of all qualities, the soldierly virtues ... .. All the great masterful races have been fighting races," he argued. There were higher virtues than those of peace and material comfort. "No triumph of peace is quite so great as the supreme tri-umphs of war." Such was the philosophy of the man who secured Commodore Dewey's appointment to the Far Eastern Squadron and alerted him before the actual outbreak of hostilities to be pre-pared to engage the Spanish fleet at Manila.

Our first step into the Philippines presented itself to us as a "defensive" measure. Dewey's attack on the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay was made on the assumption that the Spanish fleet, if unmolested, might cross the Pacific and bombard the West Coast cities of the United States. I do not know whether American officialdom was aware that this fleet was so decrepit that it could hardly have gasped its way across the ocean. Next, Dewey's fleet seemed in danger unless its security were underwritten by the dispatch of American troops to Manila. To be sure, having accomplished his mission, Dewey could have removed this "danger" simply by leaving Manila Bay. However, in war one is always tempted to hold whatever gains have been made, and at Dewey's request American troops were dispatched very promptly after the victory and arrived at Manila in July 1898. Thus our second step into the Philippines was again a "defensive" measure. The third step was the so-called "capture" of Manila, which was actually carried out in cooperation with the Spaniards, who were allowed to make a token resistance, . .

====

an excerpt from:

The Age of Excess

Ray Ginger©1965

MacMillian

During the campaign [1896 Presidential] the monetary issues pushed foreign policy into the shade, but the Republican platform did call for "continued enlargement of the Navy," and the triumphant party did contain most of the vociferous expansionists in the country. Also it brought in as Chief Executive a man who had few ideas, read no books, never publicly disputed the word of any American except for a few jibes at Democrats, and could be easily pushed. William McKinley and Mark Hanna in 1894 went to their first football game: Yale vs. Princeton. There Hanna overheard a question about his companion: "Who is that distinguished-looking man—the one that looks like Napoleon?" Perhaps never were appearances more misleading. Joseph Cannon once remarked that McKinley kept his ear so close to the ground that he got it full of grasshoppers.

But the overheard question does point to a significant craze of the depression years—a Napoleon revival. Publication of books about his personality spurted amazingly. Leading magazines competed in running serial essays and picture biographies. Major responsibility for playing up militarism must go to the Century Company and its magazine, which were preoccupied first with military aspects of the Civil War and then with Napoleon. Seemingly some Americans, overwhelmed by depression and by the futility of government, longed for a man on horseback to guide them out of the wilderness. As ex-Senator Ingalls put it in April 1896, "A man will come."

The hoped-for Hero was soon installed, at the urging of Senator Lodge, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Theodore Roosevelt at various times had lusted for war against Mexico, Chile, Britain, Spain, Germany, and any European country with a colony in the the Amiericas. During the Venezuela crisis he wrote to Lodge: "Let the fight come if it must. I don't care whether our sea coast cities are bombarded or not; we would take Canada." Early in 1897 he told the Naval War College: "All the great masterful races have been fighting races. . . ." He rather deprecated success in commerce or finance; the warlike virtues were "higher things ... than the soft and easy enjoyment of material comfort." As his mentor Roosevelt had taken Captain Mahan, whose "Preparedness for Naval War" appeared in Harper's New Monthly Magazine in March 1897-

McKinley's mind at the time was on the tariff; his first act as President was to call a special session of Congress to revise it. For) him the problem was closely tied to Cuba. The Sugar Trust, an important source of campaign funds, was forced to pay $3 to $4 more per ton for raw sugar from other sources as imports from Cuba fell 75 per cent. The Trust had powerful friends in Congress who might put forward their own Cuba policy. Also McKinley hoped to get lower duties on raw sugar in order to strengthen the argument for raising rates on other items.

. . .

“People turned from reality, as if they could not bear to admit to themselves what the facts were. Monopoly, imperialism socialism—these were denials of a creed that had been rooted in individual initiative, But it was dangerous to diagnose them.

McKinley was prone to believe his own twaddle. As the American army, in spite of its scorched-earth policy, was slow to subdue the Philippines, he went on thinking that only a small minority of Filipinos were opposed to American rule. He spoke of the need to "Christianize" them, even though nearly all were Roman Catholics. He dreamed a house in the clouds and moved into it. He even imagined that he could get the Senate to approve reciprocity treaties, but of the seven he submitted to the Fifty-sixth Congress not one was reported out of committee. On 5 September 1901 at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, just before he was shot down by Leon Czolgosz, the President told a crowd of 50,000: "We must not repose in fancied security that we can forever sell everything and buy little or nothing." But businessmen and their political allies also had delusions, and they persisted in the one to which McKinley referred.

Mark Hanna in 1900 had wanted a safe candidate for Vice-President, but the President had ordered strict neutrality, knowing that Roosevelt's military glory had made him governor of New York and would go well in another campaign. Matt Quay agreed. Thomas C. Platt, once more boss of New York, wanted to get Roosevelt out of state politics. To Hanna's question, "Don't any of you realize that there's only one Iife between that madman and the Presidency?,” they were deaf. So at McKinley's death the Presidency went to a man who called it a "bully pulpit" and preached from it. Roosevelt quickly made the White House into the chief flapdoodle factory in the nation . . .

-----

Om

K

-----

Aloha, He'Ping,

Om, Shalom, Salaam.

Em Hotep, Peace Be,

All My Relations.

Omnia Bona Bonis,

Adieu, Adios, Aloha.

Amen.

Roads End